21/10/2025

Resisting by Not Consuming: Consumer Animosity or Social Animosity?

Anthropologist Daniel Miller compares a boycott, a form of consumer resistance, to a strike, a symbol of the working class's political awakening. This is undoubtedly an uprising against a power. Therefore, by rejecting consumption, the resistance movement, situated within power relations, takes consumers from being passive actors in the market or passive spectators influenced by brand communications, but instead places them at the center, empowering them to assume an active role.

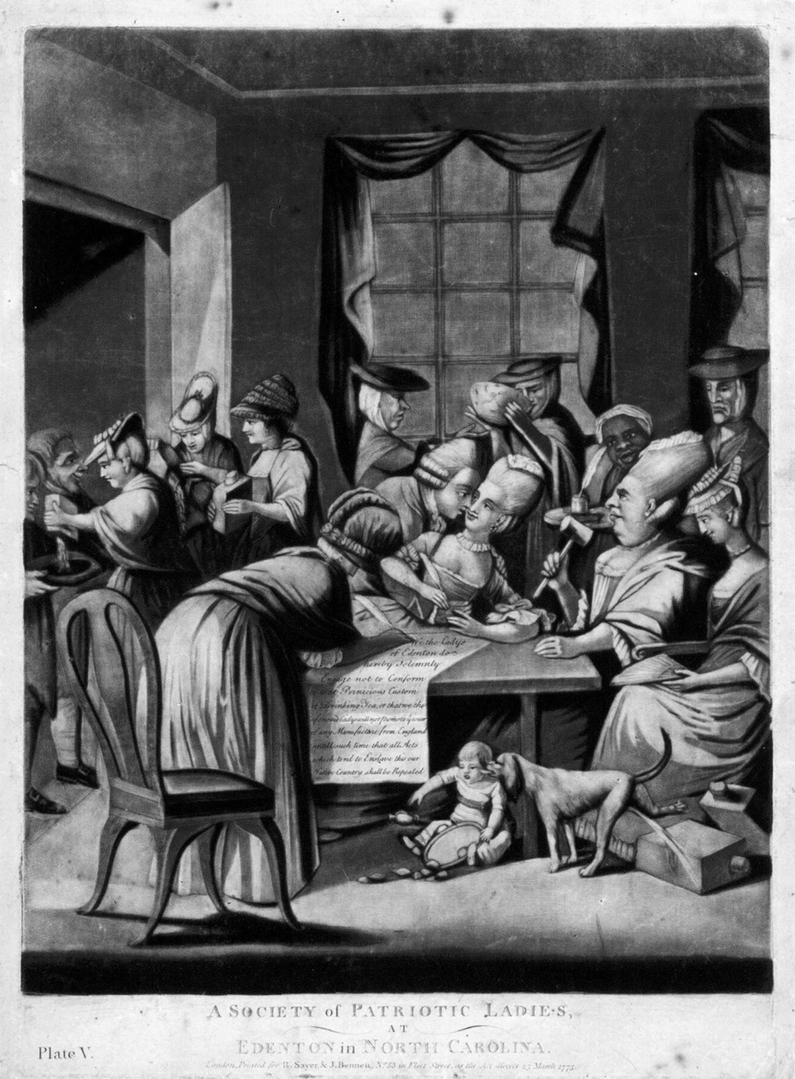

We have witnessed and even experienced, both in our country and in other countries around the world, that boycotts can be directed against a product group, or, by acquiring symbolic meanings, against a brand or a specific country's brands. Consumer boycotts, which date back to the 18th century, not only enable consumers from different locations to unite their forces, but also become more organized, particularly with the use of digital communication tools.

Digital media is perhaps the most visible element in the functioning of collective resistance in this respect. On the other hand, there is another force influencing collective resistance movements: That's social norms. Because this power is something we internalize, it's practically a part of our worldview and personal reality. Ignoring the impact of social norms on boycotts, a collective consumer resistance, means ignoring a significant part of the whole.

The "Social" Form of Consumer Animosity

Scientific studies in this field highlight the issue of "consumer animosity." Consumer animosity can also be defined as consumer anger. Apart from product evaluations, consumer animosity refers to the antipathy consumers feel toward a particular country due to past or current military, political, or economic events. Consumer animosity refers to the antipathy consumers feel toward a particular country for a variety of reasons.

In their research, "How Consumer Animosity Drives Anti-Consumption: A Multi-country Examination of Social Animosity," by İpek Nibat, a faculty member at Sabancı Business School, Tinka Krüger, Stefan Hoffmann, and Holger Gölg from Kiel University, Robert Mai and Olivier Trendel from Grenoble Business School, and Wassili Lasarov from Audencia Business School, reveal the importance of the social environment in the impact of consumer animosity on boycotts.

Behind the Scenes of the Impact of Consumer Animosity on Boycotts

In this study, published in the leading marketing journal "Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services," the authors examine the impact of social norms on product evaluations and boycotts.

With this study, the researchers define "social animosity" for the first time, introducing a new concept to the literature. The authors define social animosity as "an individual's perceptions about their social environment's animosity toward a particular country."

When you hear that your immediate circle or people in your own country are angry with a particular country, dislike that country, or speak negatively about it, your perception of this anger in your circle can trigger your own anger toward that country, leading you to boycott that country's products. These criteria are included in the eight-item scale the authors developed to measure social animosity. The researchers emphasize that the concept of animosity is different from consumer ethnocentrism.

Consumer ethnocentrism is a cognitive belief in the appropriateness and morality of purchasing foreign products, while social animosity refers to a perception of animosity toward a particular country, shaped by norms and emotions. Social animosity is defined as an individual's perceptions about their social environment's animosity toward a particular country.

The team is investigating the role of social animosity and consumer ethnocentrism in the impact of consumer animosity on boycott and product evaluations, examining animosity toward Russia and the United States. Data are collected and tested from two Western countries, Germany and the United States, and four BRICS countries, Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa. The findings show that animosity generally increases participation in boycotts and leads to negative product evaluations. However, the results vary by country. South Africans and Indians do not boycott US products, nor do Indians boycott Russian products.

This is explained by reasons such as economic attachment to the countries or the lower uncertainty avoidance of these societies. Furthermore, the study shows that for some countries, such as Brazil, India, and South Africa, as social animosity toward Russia increases, the effect of animosity on boycott participation increases.

On the other hand, consumer ethnocentrism does not moderate the relationship between animosity and boycott participation. However, for some countries, the higher the level of ethnocentrism, the stronger the impact of animosity on product evaluations.

For the full article:

Krüger, T., Hoffmann, S., Nibat, I. N., Mai, R., Trendel, O., Görg, H., & Lasarov, W. (2024). How consumer animosity drives anti-consumption: A multi-country examination of social animosity. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 81, 103990.

Prepared for publication by: Ceyda Sinağ

You can read the original article in the Faculty of Management Sciences' "From Data to Value" newsletter: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7356571296165429251